Alfred Dickens was proud of his author brother, as well he might be. He himself was just an ordinary citizen who married the daughter of the stationmaster at Strensall, a village five miles out of the city. Where they lived in York has never been discovered, but later when they moved to Norton, near Malton, while Alfred supervised the laying out of the railway between Malton and Driffield, their address according to the local directory, was ‘Derwent Cottage’.

Mr. Dickens was employed in the office of J. B. Birkinshaw, the contractor in charge of the laying out of several of Yorkshire’s new railways. This was before the building of the imposing block of railway offices in Station Road, with its weather vane proudly displaying a steam engine billowing out smoke.

Birkinshaw’s was at No. 29 Micklegate and it was at this office that Richard Chicken met Dickens’ brother.

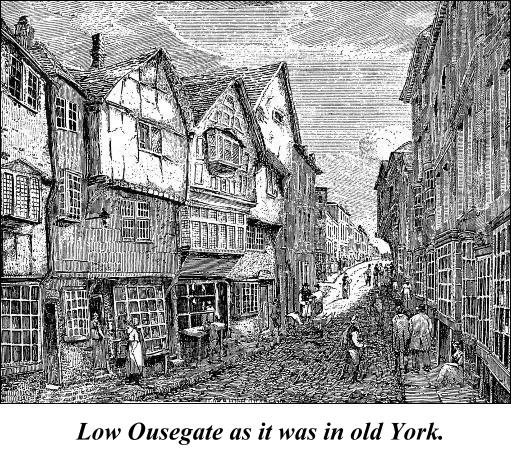

Richard Chicken was certainly an amusing, if at times somewhat pathetic, character. Born in Low Ousegate, the son of a wine merchant, he was baptized at the Church of St. Michael, Spurrergate, on August 14th, 1799, and educated at Bingley Grammar School. Keen on elocution, he joined an itinerant stock company of players and in 1824 returned to York to act in ‘The Poor Gentleman’ at the Theatre Royal. But the ‘Yorkshire Gazette’ wrote scathingly of his performance and that was his last appearance on the stage.

Failing next as a Professor of Elocution through lack of pupils, he became a clerk at the York Diocesan Registry Office. But in a short time he was again out of a job and pleading to the Lord Mayor to send him 7s. 6d. to make up his rent while at the same time apologizing most elaborately for writing such a letter on a Sunday. He also exhorted the Lord Mayor to get him a job.

‘I want employment’, he wrote. ‘Anything however irksome is better than dependence. Can you work me in your office occasionally to execute errands or what not ? I am to be relied upon. Chicken and punctuality are synonymous terms. I can vie with Pythagoras for sobriety and with Scipio for continence’.

The letter goes on to give a potted history of the circumstances which had brought him to his present state of penury and ends with a typical Chicken postscript, ‘Do you think, sir, that you have a coat or trousers in reversion? My son Quintus will call for your considerations tomorrow . .’

Eventually finding himself in Mr. Birkinshaw’s office, he worked tolerably well for a time, but soon he grew tired of his steady ‘9 till 6’ job ‘without intermission or interval (excepting dinner hour)’, and he would leave letters about on his colleagues’ desks imploring them for money so that he could take a rest.

But when he went a step further and wrote to the Chief of the Department (‘to bring before you the fact that I have for a considerable period suffered from disease in the region of the heart’, and that ‘very close application to the desk with its accompanying contraction of the chest operate against me") in the hope that ‘you can give me an appointment where I might have more exercise and less restraint’, he received, to his consternation, not a transfer but his notice. And immediately concocted a series of letters begging to be reinstated. but without result.

FOR several years the Chickens lived on St. Mary’s Row, Bishophill, hatching out baby Chickens at regular intervals, and according to the record of a neighbour, bathing them every Sunday morning in the yard in full view of everybody who wanted to look.

Five of the brood died tragically of typhoid while they were at Bishophill; the gravestone in the churchyard of St. Mary’s listed them as Alexander Jordan, Gustavius, Nicholas Huddlestone, Louisa Adelaide, and Jesse Quartissimo, until it was removed when the church was demolished a few years ago.

Later, the family moved to Bilton Street in Layerthorpe ; there were still so many little Chickens that they had to rent two houses to accommodate them all. By that time Richard was known all over the city for his Micawberish way of life and for his inimitable begging letters.

Early readers of David Copperfield who knew him constantly noticed incidents in the life of Micawber which closely resembled Chicken’s ways. For instance, while Traddles was putting on his great coat, Micawber took the opportunity to slip a letter into Copperfield’s hand with a whispered request to ‘read it at leisure’; Chicken frequently did this with friends and acquaintances.

Again, Micawber tells Copperfield about the pawning of spectacles—Mrs. Chicken once wrote to a lady that ‘Mr. C. walked off with my spectacles . . . but I have redeemed them’. Yes, Mrs. Chicken, taking a leaf out of her husband’s book, took to writing begging letters, too, and presumably this way of getting an income paid off for many a day, for they always seemed to keep one step ahead of the bailiffs.

But towards the end of Chicken’s life the inevitable happened. People ceased to be amused by him and, being only irritated, left the family to get on as best they could. And so, Chicken found himself in the Workhouse—and his wife took herself and the children to Leeds where she tried to open a school, though without success. In the meantime, her husband continued to engage in his usual pastime and flamboyantly phrased missives found their way to all parts of the city.

In the end he even ran out of writing paper; his last letter, written to a Mr. Simpson, was a pathetic appeal written on a flyleaf out of a book.

It ran, ‘You have perhaps heard that I am in the Workhouse, and in a bad condition of health. I don’t expect to come out alive. The confinement and the society will kill me: moreover, I cannot eat the porridge, which constitutes our breakfast and supper; but we are allowed to have coffee and tea if we find it ourselves. . . I desire my respects to the clerks in the office, and hope they will have the humanity to raise me a trifle to procure a morsel of coffee and sugar . . .’ and with a truly Chickenish touch he appended a postscript that ‘the society of idiots, the ignorant and the profane, is not adapted to me :—poor Chicken !’

Poor Chicken indeed! One hopes he got his coffee and sugar. If only as a reward for the amusement which undoubtedly his letters had occasioned over a period of years.